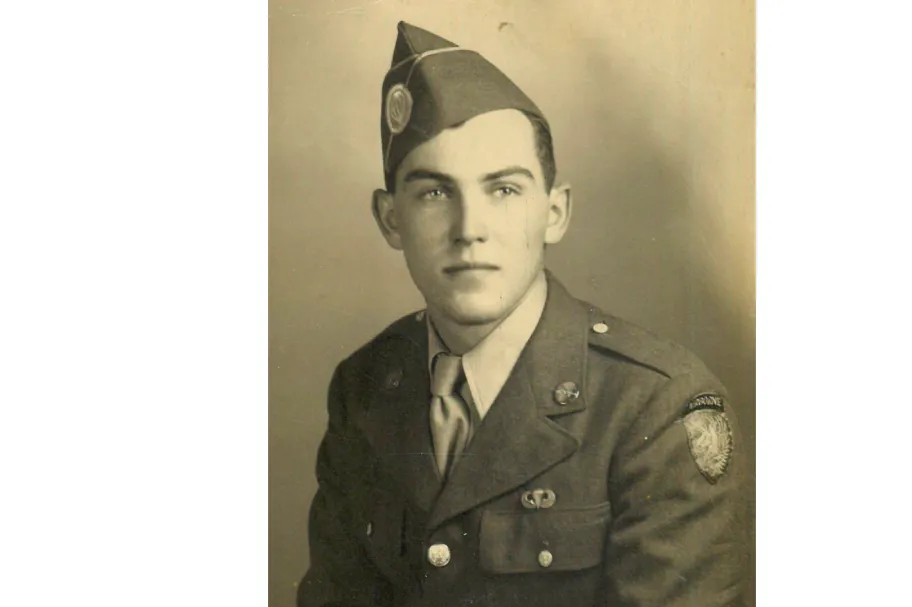

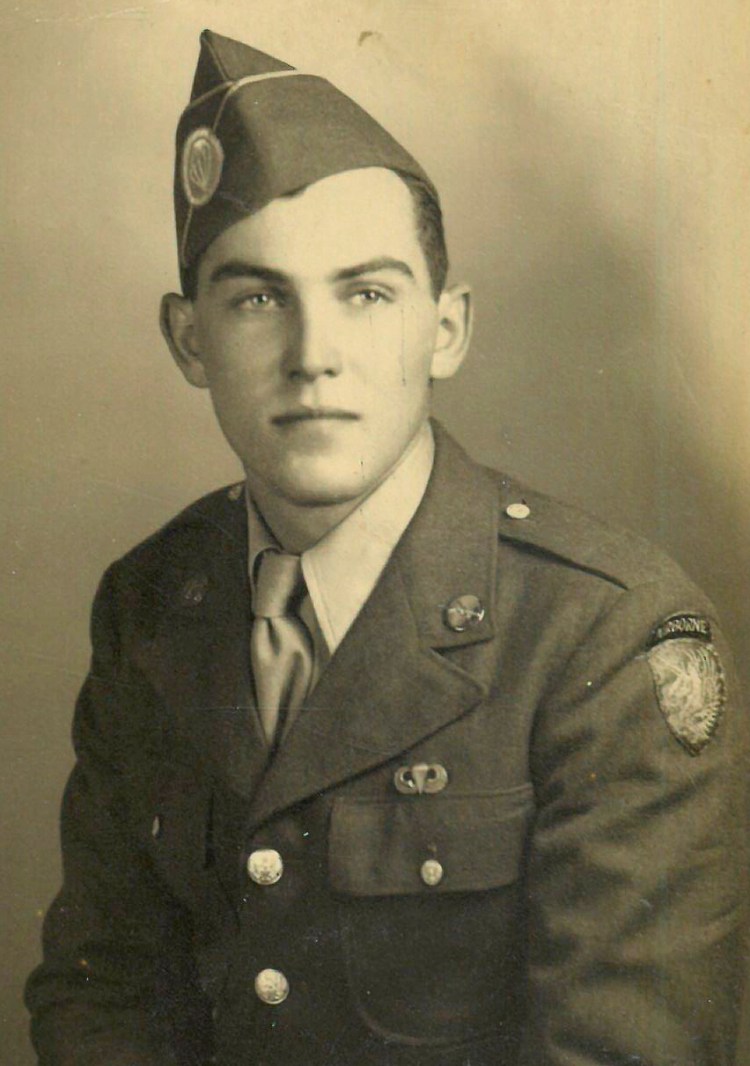

This undated photo provided by the Bragg family shows Pfc. Roland L. Bragg. A Pentagon spokesman said Monday Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was renaming a special operations force base to honor Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, who he said was a World War II hero who earned the Silver Star and the Purple Heart for his exceptional courage during the Battle of the Bulge. Associated Press

During the Battle of the Bulge, when American troops fought off a surprise German offensive near the end of World War II, a paratrooper named John Martz lay badly injured on a stretcher in a snow-covered stone barn in Belgium with a few dying comrades.

He was part of the Army’s 17th Airborne Division that had been placed in a quiet sector of the front to rest and recuperate.

Instead, the ground-bound paratroopers found themselves in a pitched battle, pounded by artillery as enemy troops moved to surround them.

Martz didn’t know if he would pull through.

Then another soldier, Roland Bragg, who hailed from Maine, showed up outside with a stolen German ambulance, determined to help.

With that, Bragg set off an unlikely series of events that led to Martz’s rescue, a Silver Star for bravery and then, after a quiet life back in the Pine Tree State, he suddenly rose this week to national prominence a quarter of a century after his death in Nobleboro.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth ordered the Army on Monday to change the name of Fort Liberty in North Carolina to the name it carried for more than a century: Fort Bragg — but this time for a whole different namesake.

In 1918, the military named the fort after a Confederate general, Braxton Bragg, a native of North Carolina who took up arms against the nation he had sworn to serve during the Civil War. Two years ago, as part of a wave of revisions to haul down monuments to the leaders of the South’s failed rebellion, the name was changed to Fort Liberty.

But Fort Liberty didn’t sit well with many, including President Donald Trump, who vowed during the campaign to change it back to the old name.

No doubt recognizing that again naming the fort after a traitor might raise some concerns, Hegseth said Monday that the new Fort Bragg wasn’t named for the long-dead general.

It was instead named for Pfc. Roland Bragg, born in Sabattus and a lifelong Mainer who died in 1999 with little acclaim.

Debra Townsend-Sokol of Nobleboro said Tuesday that her father would be “very humbled” and surprised at the decision to name the fort after him.

She said he never made much of his military service — recalling only one Christmas when he told the story of what happened during the Battle of the Bulge.

Townsend-Sokol, who lives in a house her father, a mechanic and builder, moved to its present location, said he was a good dad and a good man.

She remembered how he would organize ice skating parties on a local pond where he’d buy 10 pounds of hot dogs and many marshmallows for everyone to partake in.

She said her father only lived in Sabattus for a few years when he was little. He spent most of his life in Nobleboro, Townsend-Sokol said, graduating from Waldoboro High School in 1943.

His obituary said he was a member of the Grange, the American Legion and served for a time as a Nobleboro selectman.

Bragg “never tired of doing things for others,” his obituary mentioned.

One of those moments, in the winter battle near Bastogne, led to the honors bestowed on him.

“We were spearheading our battalion then,” Martz told the North County Times of Oceanside, California, in 1994.

“We were way up in there and the Germans just came in around behind us,” he said during a reunion with his savior, the first time they’d seen each other since the battle a half century earlier.

They were running out of ammunition and medical supplies as the Germans pounded their positions.

“I remember being blown in the air six or eight times by the big-gun shells,” Martz remembered. Then he found he couldn’t get up off the ground.

He said somebody must have carried him to the barn or he would have frozen to death in the snow.

The few American soldiers who were still capable of fighting on were preparing to move out while they still could.

“They were going to leave us for prisoners,” Martz said. “We thought that was the end of it for us.”

Then Bragg appeared.

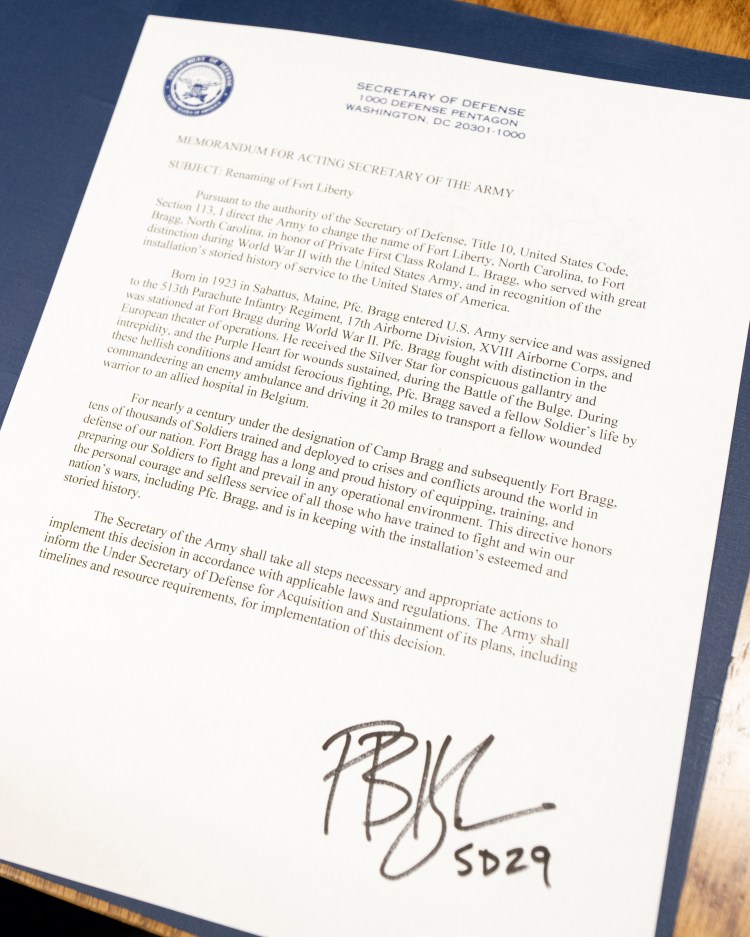

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s signature is seen on a memorandum reversing the name of Fort Liberty back to Fort Bragg in North Carolina, while flying in a C-17 operated by the 300th Airlift Squadron en route to Stuttgart, Germany, Feb. 10. U.S. Department of Defense

Townsend-Sokol said that when her father told the family the tale, he said a German moving in recognized the danger posed to the wounded Americans.

He told Bragg to “hit me in the head and take off” in his vehicle to transport the men to a hospital.

So Bragg did just that.

Another of his daughters, Linda French, once said that her father had been taken prisoner briefly but the German who held him was a fellow Mason so he let him go — and took his vehicle, too.

Martz recalled that someone loaded him and three others into an ambulance and raced through withering enemy fire to reach a hospital behind friendly lines, some 20 miles away.

He spent a week and a half there recovering before heading back to the front lines, always wondering how he got out of the barn to safety.

As the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge approached, Martz found a list of survivors from his division and began writing to them.

One wrote back, he said, to tell him he remembered seeing Martz on a stretcher in that barn but nothing else.

Bragg got one of Martz’s letters.

“I remember sitting at the kitchen table reading that letter,” Bragg told the California paper, “and chills went up and down my spine. I thought everyone died.”

Indeed, in the first account of the improbable rescue, in John Eisenhower’s “The Bitter Woods” history of the battle, it said all the wounded had been killed. Bragg had no reason to think otherwise until he got a letter from Martz.

The two later met in California, an event that left Bragg feeling “very pleased,” according to his daughter.

Bragg himself was injured in the fighting, but not badly.

“The only thing I got was a burn on the side of my head where a bullet went by,” Bragg said. “The Lord was looking after me that day.”

Both men went on to fight another day, parachuting into Germany during the last days of the war in 1945.

And then they went home.

Bragg got a Purple Heart for his wound and a Silver Star to honor his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity.”

But he never talked about it, save for that one Christmas Day.

Bragg told the California paper he joined his father and brother in an auto parts business, got married and later started his own auto body enterprise in Nobleboro.

He wound up owning a house-moving company.

In short, Bragg was never one to brag. He did his job, and like so many veterans of World War II, he just got on with living.

All in all, whatever the reasons, he did something extraordinary, though he might well have protested the notion.

And unlike the Confederate general, he represented his country with honor.